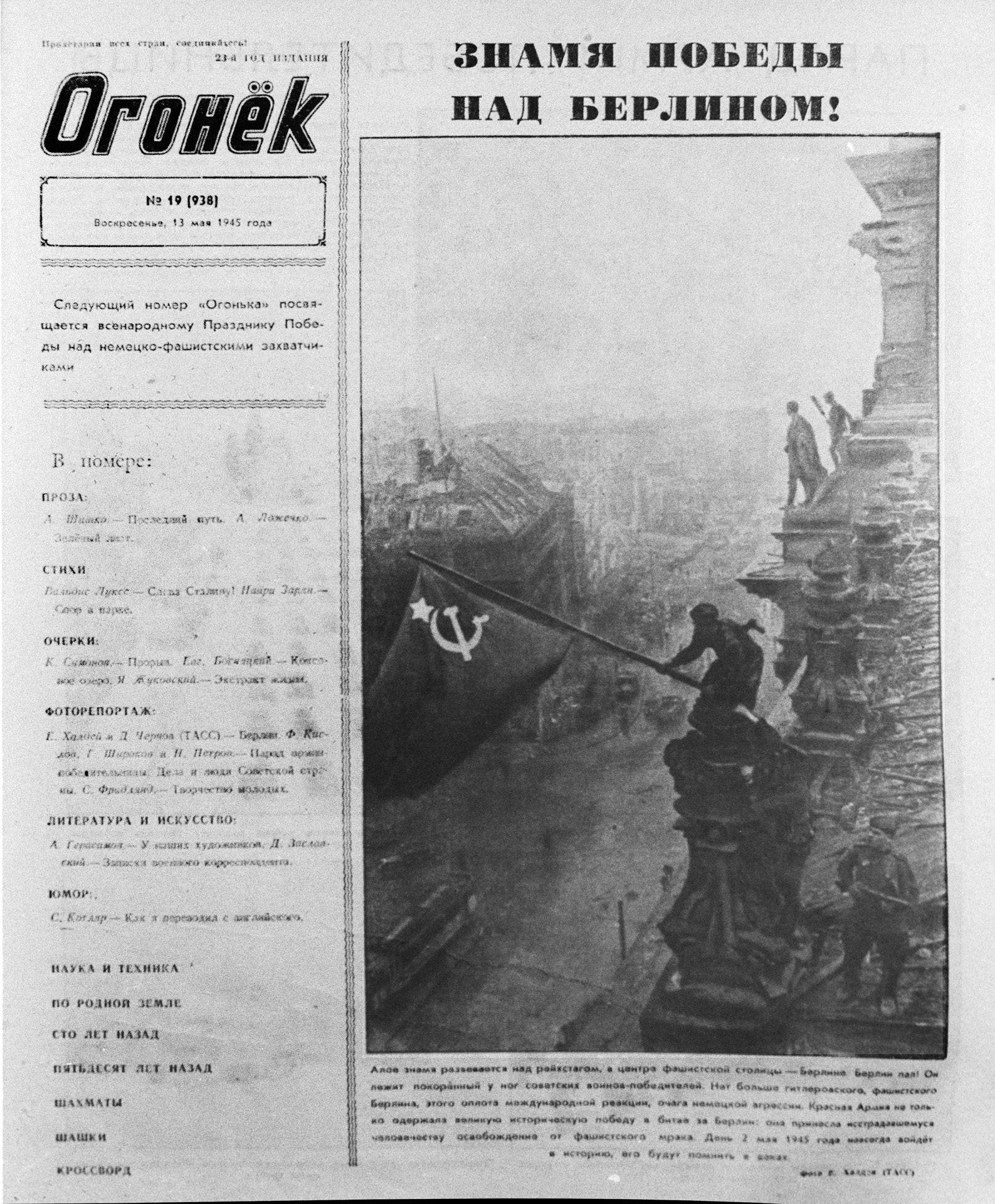

Raising a Flag over the Reichstag

1945

As hostilities approached their conclusion, it became inconceivable for me to return from an assignment without photographic evidence of banners over the cities we had liberated or captured. The flags of Novorossiysk (Russia), Kerch (Crimea), and Sevastopol (Ukraine), reclaimed precisely a year prior to our victory, remain particularly dear to me.

For an extended period, I contemplated my potential contributions to this prolonged conflict: what could surpass the significance of capturing the Victory Banner above our vanquished foes? Such an opportunity indeed presented itself when, upon my return to Moscow from Vienna, the editorial team at TASS Newsreel — formally known as the Soviet Telegraph Agency of Communication and Messages — assigned me to travel to Berlin the following day.

For an extended period, I contemplated my potential contributions to this prolonged conflict: what could surpass the significance of capturing the Victory Banner above our vanquished foes? Such an opportunity indeed presented itself when, upon my return to Moscow from Vienna, the editorial team at TASS Newsreel — formally known as the Soviet Telegraph Agency of Communication and Messages — assigned me to travel to Berlin the following day.

Orders are orders, thus I promptly began preparations, aware that Berlin represented the ultimate culmination of the war. My compatriot and friend, tailor Israel Kishitzer of Leontievsky Lane, assisted me in assembling three flags from red tablecloths procured from the local committee of the Workers’ Party, courtesy of TASS custodian Grisha Lyubinsky. I personally fashioned the symbols of the star, sickle, and hammer from white fabric. By dawn, all three banners were prepared. I hurried to the airfield and departed for Berlin.

The period was marked by chaos. I was hardly the only one navigating the tumult of Berlin with a camera; photojournalists and cameramen, often oblivious to the peril, sought the perfect photograph. A remarkable narrative unfolded at the Reichstag: impromptu volunteers, armed with makeshift flags crafted from the red covers of German duvets, surged toward the Reichstag, affixing their banners wherever possible — be it upon a column or within a window.

Interestingly, in any conflict, the prime objective is typically secured first, followed by the hoisting of flag. Here, the sequence was reversed. My desire to survive was strong, yet I was equally as eager to embrace the notion that the war had concluded, and no harm would befall us. You might recall that Mikhail Egorov and Meliton Kantaria were the pioneers in erecting the Victory Banner. Indeed, several banners were prepared in Berlin and distributed among the divisional headquarters likely to reach the Reichstag’s main edifice. Nine divisions advanced to storm the structure.

It is rumoured that approximately 40 different banners were raised over the Reichstag during the assault, though the number of volunteers was undoubtedly higher. In any event, Egorov and Kantaria did not ascend to the dome alone; they were accompanied by battalion deputy commander Lieutenant Alexei Berest and a contingent of sub-machine gunners led by Senior Sergeant Ilya Syanov. Berest, noted for his formidable strength, escorted the flag bearers to the dome, shielding them from unexpected threats.

Overall, the act of raising the flag atop the Reichstag emerged from a collective endeavour rather than an individual achievement. However, history books predominantly commemorate only Egorov and Kantaria. At the time, I was unaware of the red banner’s presence; on the morning of May 2nd, the vicinity of the Reichstag remained engulfed in conflict…

Overall, the act of raising the flag atop the Reichstag emerged from a collective endeavour rather than an individual achievement. However, history books predominantly commemorate only Egorov and Kantaria. At the time, I was unaware of the red banner’s presence; on the morning of May 2nd, the vicinity of the Reichstag remained engulfed in conflict…

I did not set out to be the first to ascend – reaching the rooftop with my ‘tablecloth’ banner was imperative. Therefor, with the flag concealed within my attire, I stealthily navigated around the Reichstag, entering through the main doorway. Combat persisted nearby. Upon encountering a scout team led by Commander Ivan Shevchenko, he wordlessly produced his flag instead of offering a greeting. Volunteers Alexey Kovalev from Kiev, Abdul Hakim Ismailov from Dagestan, and Leonid Gorychev from Minsk and I climbed to the rooftop.The scout team positioned themselves securely.

I immediately sought an ideal location for photography. The dome was ablaze; smoke billowed below, flames and sparks leapt upward, making proximity nearly impossible. I then sought an alternative vantage point. A suitable flagpole was located, and Kovalev, the youngest, assumed the role of flag bearer. Clinging to a narrow parapet, I commenced photography. I shot two rolls of film. I captured images in both horizontal and vertical formats. While filming, I instructed Alexey to rotate the flag in various directions. However, the imagery proved ineffective. The flag needed to symbolise victory. Consequently, I directed Kovalev to climb one of the towers and angle the flag over the city. Despite the risks, Alexey ascended, and Ismailov, to prevent him from losing his balance, supported him by the legs as he leaned out with the flag. I captured several photographs of this poignant moment—the Banner of Victory over the Reichstag!

Undoubtedly, the endeavour was fraught with danger, but once we descended and observed our flag atop the building we had just vacated, we realised our risks had not been in vain.

Recognising the importance of publishing this image, I immediately returned to Moscow. Upon viewing the negatives featuring the flag, the editor-in-chief of the TASS agency was elated. However, he promptly interjected, ‘Stop! Zhenya, Captain Ismailov is wearing watches on both hands!’ — they became visible as he supported Kovalev. ‘This must be addressed; otherwise, it might be misconstrued as looting. Erase the watch from his right hand.’

I reluctantly complied, using a needle to make the alteration. In this modified form, the photograph has been disseminated for 50 years in both the Soviet press and internationally, becoming an emblem of Victory.”

Kovalev and Khaldei did not receive any accolades for this image during their lifetimes. Boris Yeltsin posthumously awarded Ismailov the title of Hero of Russia in 1996; he became a national hero in Dagestan and led a contented, long life.

In 1995, the BBC facilitated a reunion between Kovalev and Khaldei in Red Square, capturing the emotional encounter in a brief video. Coincidentally, they passed away in the same year: Kovalev in June, and Khaldei in October 1997.